- Home

- Andrew Anastasios

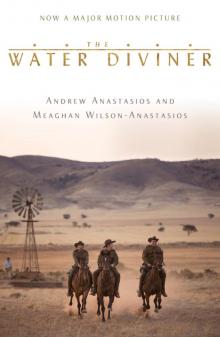

The Water Diviner

The Water Diviner Read online

About The Water Diviner

Constantinople, 1919. Joshua Connor, an Australian farmer, arrives in Turkey to fulfil a pledge made on his wife’s grave – to find the bodies of their three sons, lost in battle at Gallipoli, and bring them home.

In the enemy city Connor meets Orhan, a mischievous Turkish boy, and his mother Ayshe, who is struggling to keep her family hotel afloat and rebuild her life after the war.

Connor can trace life-giving water under the earth, but finding his sons at Gallipoli seems impossible when faced with the gruesome landscape of sun-bleached bones and rotting uniforms. But a Turkish officer gives the broken father hope where there was none – Connor’s eldest son may still be alive.

As Connor risks his life travelling into the heart of Anatolia one question haunts him: If his son is alive why hasn’t he come home?

This novel tells the complete story of The Water Diviner and is based on the original screenplay by Andrew Anastasios and Andrew Knight. It is inspired by true events found within personal accounts and official records from the Great War.

Contents

Cover

About The Water Diviner

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Acknowledgements

About Andrew Anastasios and Meaghan Wilson-Anastasios

Copyright page

For Roman and Cleopatra, and the history that lives in you.

PROLOGUE

A match flares in the dark. It dies a swift, hapless death.

A second, this one shielded by a cupped hand, licks a candlewick until it catches. As a halo of orange illuminates the dugout, a quick, frosty breath snuffs out the match. With strong manicured fingers a man prises open a fob watch, glued shut with grit and sweat: five minutes to five. He slips the watch into his tunic pocket. A second thought. He retrieves it, polishes the casing on his rough woollen sleeve and places it in a small metal trunk on his bed. Every instinct tells him he won’t be needing the watch after this morning. If everything goes as expected, he won’t be needing anything much at all.

The man shuffles around the small bolthole, picking up his meagre personal effects and packing them into the trunk. It surprises him how austere the world of even the most cultured man can become. When life is distilled down to its most basic elements, it’s remarkable how little you really need. Some officers like to confect a home away from home, surrounding themselves with familiar comforts: their favourite cologne, a gramophone, coffee-making utensils, their library. He resists the urge. He never wants this to feel normal, never wants to mistake what they do here for civilised. Nevertheless, this lair has been his home since May, through a dysentery-wracked summer and a wretched autumn. Now a sodden winter is smothering his resolve. It snowed last month and an eighteen-year-old sentry was found frozen at his post in the morning. Not how you expect a man, young or old, to die in war.

He has packed the trunk in this way, the same scant items in the same order, eight times since they landed. He could leave it for someone else. For after. But the packing has become something akin to a rite, a ceremonial declaration. Everything is in order. I am ready for the worst. I dare you.

He flicks the pages of his diary, water stained, muddy and precious. He recalls his first entries, considered and self-conscious, every word a labour. Yesterday’s entry – I woke early. Bitterly cold. Reported to colonel. After seven months of suffering, there’s nothing left to say. He wipes the cover with his hand and drops it into the trunk, then places a family photo on top. In his palm he juggles a closed pinecone like a grenade before putting it, too, inside the chest. His shaving bowl, razor and brush follow. He lifts a woman’s scarf up to his nose, breathing in the scent of his wife. Or the memory of her. Who knows for sure anymore? He wraps it around a sheaf of papers – a letter – then drops them into the trunk and closes the lid.

As he moves to the table where his revolver lies, the flickering candlelight catches his epaulettes and the hilt of the sword strapped to his side. He’s a career officer, a major, a forty-seven-year-old man of quiet resolve. Now weary and taut, he is on the brink of ordering yet another pointless assault on the enemy trenches at Gallipoli. He has done this countless times before. But today, inexplicably, it unsettles him.

He knows this attack may well cost him his life. Which is nothing new. Snipers on both sides routinely target officers, to decapitate the lumbering enemy on the charge. Certainly he knows hundreds of his men will perish in the next thirty minutes for no particularly good reason. Whatever scant centimetres they advance this morning will be stolen back by the enemy tomorrow. With all the to-ing and fro-ing at Lone Pine, the front lines haven’t moved for four months. There was a time when he was disgusted by the profligate waste of life. Now it just exhausts him.

Light filters through the coarse hessian curtain that acts as his door. He hears a guttural cough, a none-too-subtle reminder from his sergeant. He smiles to himself. Hat on, pistol holstered and sword slapping his leg, the officer pushes back the curtain and steps into the pre-dawn light.

A rugged face appears before Major Hasan. It is his staff sergeant, Jemal, a weather-beaten lion of a man and a veteran of too many campaigns. He speaks in Turkish, fog on his breath.

‘Five minutes?’

Hasan looks past him and down the muddy Ottoman trench at his ragtag army. Whiskered grandfathers stand beside terrified teenagers, farmers beside bank clerks from Stamboul. Some wear full uniform, others are clad in a motley mismatch of civilian clothes tricked up with military-issue jackets, trousers or belts. The Ottoman Government is still recovering from the Balkan War and is desperately low on uniforms and supplies. Many of these conscripts are standing in the clothes of dead men, the blood washed away and bullet holes worn as lucky charms. Surely lightning can’t strike twice. The fortunate wear boots – often salvaged from the feet of fallen comrades – but the rest have wrapped their bare feet in cloth against the cold.

‘Wait for the sun,’ says Hasan with a nod.

Jemal salutes and the message is relayed quietly along the trench with a whispered word or a gesture. Soldiers shake hands and kiss their comrades, fathers or sons on both cheeks. An imam, bearded and solemn, blesses men as they huddle around a brazier; the heat of the flames does little to disperse the frost of mortal fear.

The bone-chillingingly cold air is still. Silent. Jemal supervises as scaling ladders are raised against the trench wall and m

en line up at their bases. Their tension is palpable. Teeth chatter, not just from the cold. The acrid smell of urine and the stomach-churning sweet tang of the decaying dead in the ghastly stretch of land between the two front lines pollute the morning air.

Hasan spots a young boy, lost in an oversized tunic, his boots on the bottom rung of his ladder. He is determined to be first over the top. As the major strides towards him the boy looks into the mud, deferring to the senior officer.

‘Soldier, what is your name?’ asks Hasan sternly.

‘Yilmaz,’ the boy replies into the dirt, adding, ‘from, Mardin, sir,’ as an afterthought.

‘Fetch my binoculars, Private Yilmaz from Mardin. They’re in my dugout.’

‘But Commander, I’ll miss –’

‘Do it,’ demands Hasan, cutting him short.

Reluctantly Yilmaz gives up his place at the front of the line and makes his way along the trench. Major Hasan watches the boy disappear and then steps onto his ladder and chances a look over the top of the sandbags at the enemy line. The grim expanse of no-man’s land is dusted with frost; infinitesimally small crystals reflect the first blush of dawn’s pale light. A distant rifle cracks, shattering the unnatural silence, and Hasan ducks automatically. He composes himself and signals to an old bandleader, who is resplendent in his tattered velvet jacket and meticulously waxed handlebar moustache. A handful of drummers and trumpeters gather in a huddle, and the bandmaster thrusts a flag into the air. A trumpet wails and the band strikes up a discordant anthem, the signal to charge. In a chaotic, adrenaline-fuelled scramble, men surge up the ladders and over the trench wall crying, ‘Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!’

Hasan has timed the assault perfectly, using the rising Aegean sun to dazzle the enemy as his troops charge across no-man’s land. Hasan climbs over the sandbags, with Jemal puffing beside him like a swimmer coming up for air. Ottoman soldiers cry out at the top of their lungs around them, expelling their fear and anxiety. Those with guns fire blindly into the dawn light before them. The rest brandish farm implements and handmade pikes, waiting for the man beside them to fall so they can seize his rifle and make it their own.

The Australian front line is barely the length of a tennis court away but the ground is sodden and uneven, and punctuated with craters and bloated corpses that form a gruesome obstacle course for the running men. And soldiers do fall, some tangled at the ankles by coils of razor-sharp wire curling out of the mud, others dropping into shell holes filled with a hideous soup of stagnant water and disarticulated body parts.

In the confusion they can hear guns from the enemy trenches spit and buck. The band is charging across the field in a loose formation, still playing its defiant, dissonant song, but now a few instruments short. The bandleader waves the colours of the 47th Battalion like a red rag to a bull.

Revolver in hand, Hasan stumbles across no-man’s land, Jemal at his side. At any moment he expects to feel the searing heat of a bullet and the mud in his hair as he is knocked onto his back. He knows his sergeant will be happy if he can just get his cavalier commander to the enemy trench in one piece. He can almost hear Jemal thinking, Why can’t the major be like most men of his rank and stay behind the line? That’s what binoculars are for.

They have caught the Australians off guard with the early hour. Hasan imagines them still huddled under their khaki coats like street children as the Turkish boots drop down beside them, spraying mud. Bayonets make for a rude awakening. In the last assault Hasan watched as most of his men were mown down by snapping machine-gun fire before they took a step. He lost count of how many fell back into the trench, killed before they even cleared the sandbags. Are the Anzacs just waiting, biding their time, before launching an unholy barrage? Ahead, Hasan can see the first wave of his attack nearly at the enemy line, bayonets raised and bellowing at the Australians, daring them to do their worst.

And then, through the December mist, it happens.

Suddenly the raging Turks all stop in unison. The sound of gunfire peters out. The yelling subsides as perplexed soldiers stand in silence and look down into the enemy trench.

Jemal nudges soldiers aside as Hasan makes his way through his troops to the edge of the trench. From high up on a sandbag he looks down in disbelief.

There is no one there.

Hasan, conditioned to always expect the worst, is suspicious.

‘It’s a trap. It must be.’

Jemal shrugs. ‘If it was, we’d know by now.’

Hasan drops into the Anzac trench and Jemal joins him, both wary of booby-traps. Perplexed and confused, the men of the 47th watch on in silence.

A sudden blast from a rifle propped on the edge of the trench, and the men dive for cover. Jemal and Hasan barely flinch. The two men examine the unmanned gun, smoke still spiralling from its barrel. Hasan sees that it’s been set up to shoot at the Ottoman front line automatically. The .303 is fired by a clever system of water-filled tin cans punctured so that they empty gradually, until they pull the trigger. He can’t help but admire the ingenuity.

Jemal reloads the rifle and unscrews the stopper on his canteen, about to pour water into one of the cans. He pauses, looking down the barrel at a cluster of soldiers watching at the business end of the rifle, and waves them away.

‘Move or be martyred,’ he bellows.

The men have learned that an order from a man as rash as Jemal is ignored at their peril. They scramble out of the way as he empties his canteen into the can tied to the trigger. The gun fires with a loud crack. Jemal nods, impressed.

Hasan continues along the trench, passing a table set for a game of chess; one white pawn pushed two squares towards the enemy line. A note in English sits under the piece and reads, ‘Your move, Abdul.’ Hasan gives a wry smile. Another time, another place, he might have enjoyed meeting this chess player. Strange to think that in the midst of the dehumanising chaos of war, an enemy soldier found solace in such a civilised pastime.

Jemal appears, wielding a cricket bat like a club.

‘A weapon?’ asks Hasan.

‘I watched them play this pointless game near the beach, between barrages.’ Jemal holds the bat over his shoulder and swings it through the air before studying it intently. ‘Whatever it was, they took it more seriously than the war.’

They are interrupted by a distant cheer, and peer over the sandbags to see the bandleader waving his flag and dancing. He is pointing out to sea. Hasan climbs a ladder and raises his binoculars to see a white wake cutting through the ink-black Aegean and trails of smoke from the departing Anzac troopships as they make a beeline for Greece.

As Hasan’s men realise what has happened, shocked silence gives way to waves of celebration. Just moments before, they had resigned themselves to the inevitability of sudden and violent death. The release of tension ignites the gathered Ottoman troops like a lit fuse. Some men fall to their knees in silent prayer. Others weep and congratulate their friends for surviving. But most cheer and shoot their guns into the air, crying, ‘Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!’

Today, Hasan thinks, after months of being a passive bystander, God truly is great.

Hasan sits on a sandbag and leans his head back against the trench wall. He takes in the significance of the moment, and doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry. After 238 dreadful days of staring at each other across the ditch, strafing each other with machine guns, picking each other off on the way to the latrines, mining each other’s trenches, listening to each other’s wounded bleed out in no-man’s land, and finally tossing gifts of cigarettes and food from trench to trench, the invaders have skulked away in the night. He knew they must, before the winter floods washed them off the cliffs that they had clung to so tenaciously. This is a good thing; it is what they have been praying for. But for a moment he feels bereft – cheated. The enemy has defined him, given him his purpose. But now, to a man, they have suddenly stolen away under cover of darkness without giving him the opportunity to salvage anything positive from thi

s cursed morass.

Yilmaz, the boy soldier, appears, running across noman’s land, out of breath.

‘Sir, your binoculars. I could not find . . .’ He trails off as he spots them hanging around the major’s neck.

With a half-smile Hasan replies, ‘Private Yilmaz from Mardin, today was not your day to be martyred.’

The band launches into a Turkish folk song as soldiers throw down their guns and start singing and dancing.

CHAPTER ONE

A man paces across a vast paddock, under a vaulting indigo-blue sky. He performs an oddly choreographed dance; first striding in one direction, then sidling in another; backtracking slowly before turning.

From beneath a dusty brim his eyes scan the rust-red soil. He is blind to the beauty of the sunrise as the first long fingers of rose gold stretch across the Mallee plains, glinting off the strands of parched summer grass.

He stops abruptly, and peers down at his clenched hands like a churchgoer who has forgotten the words. How, he wonders, has he just noticed? Knotted, with skin like bark, they are hands much older than his forty-six years.

In each fist he clasps a short length of brass tubing, polished to a warm patina from years of use. A foot-long length of wire bent into an L-shape protrudes from each tube, like grasshoppers’ feelers. As the man moves, the antennae swivel and scout. He follows their lead, weaving across the paddock and watching for the moment when they converge and cross. It will be right there that he will find it, but he never knows how deep down it will be.

Joshua Connor is as tough and unyielding as the land he calls home. Tanned like hide, he is tall with the broad shoulders and well-muscled chest of a man conditioned to long days labouring under the Australian sun. He has neither the time nor the inclination to place any stock in life’s mysteries. To him, water divining is just something he can do – just as it was something his mother could do, and her father before that. Take it back a few generations and they would have been called water witches. A bit further back in time, and most likely they would have been burned at the stake. But here, today, in the dry and unforgiving Australian outback where water is life or death, Connor’s strange gift is as precious as it is inexplicable. Unyielding and irascible, he is not the most popular man in the district but no one would ever deny that Connor’s baffling ability to sense hidden subterranean water has saved many a local family.

The Water Diviner

The Water Diviner